Mac and Alan were my great aunt and uncle. They stood in for grandparents. Mac’s real name was Hilda but her maiden name was McRae and she’d been Mac since about 1912.

Mac wore cotton print dresses and sturdy shoes and clip-on peacock earrings that looked majestic and painful. Alan was ancient and deaf and moved like a marionette with dangling hands and wavering feet. I loved them both, but I worshipped Alan.

My mother took me and my brother to the city to see them every few months and the visits always went like this:

We would park in the back and knock on the side door. The house had once looked out over farm land. Now, in the 1970s, it faced an expressway.

Mac would bring us into the kitchen, where she had a tray laid with coffee cups and rock cakes, that were exactly as they promised—hard, dry, disappointing. The coffee was made with instant powder stirred into boiling milk. The downside was the rubbery skin that formed as it cooled. The upside was that we were allowed to drink it.

While the milk was boiling, if the timing was right, we would get to see the cuckoo come out of the cuckoo clock. We never stayed longer than an hour, so the timing was crucial.

The coffee tray would be carried to the front room, where Alan would be watching the cricket over the roar of traffic. Mac and my mother would talk about Cousin Helen who was a nun doing Good Work on some Pacific Island. My brother and I would sip our rubbery coffee, pretend to nibble the rock cakes, and wait for Alan to rescue us.

Come on then, he’d say, and he’d put hats on our heads and trowels in our hands and we’d step out to the garden. There, beneath the peach trees and apricot trees, among the winding paths and raised beds, you forgot all about the expressway. Time seemed to slow. There were sprinklers to be moved or to jump through, depending how hot it was and how brave we felt. There were strawberries to pick and lettuces to thin and zucchini on the way and every foot of the garden was given over to growing something useful and practical and edible, with one exception.

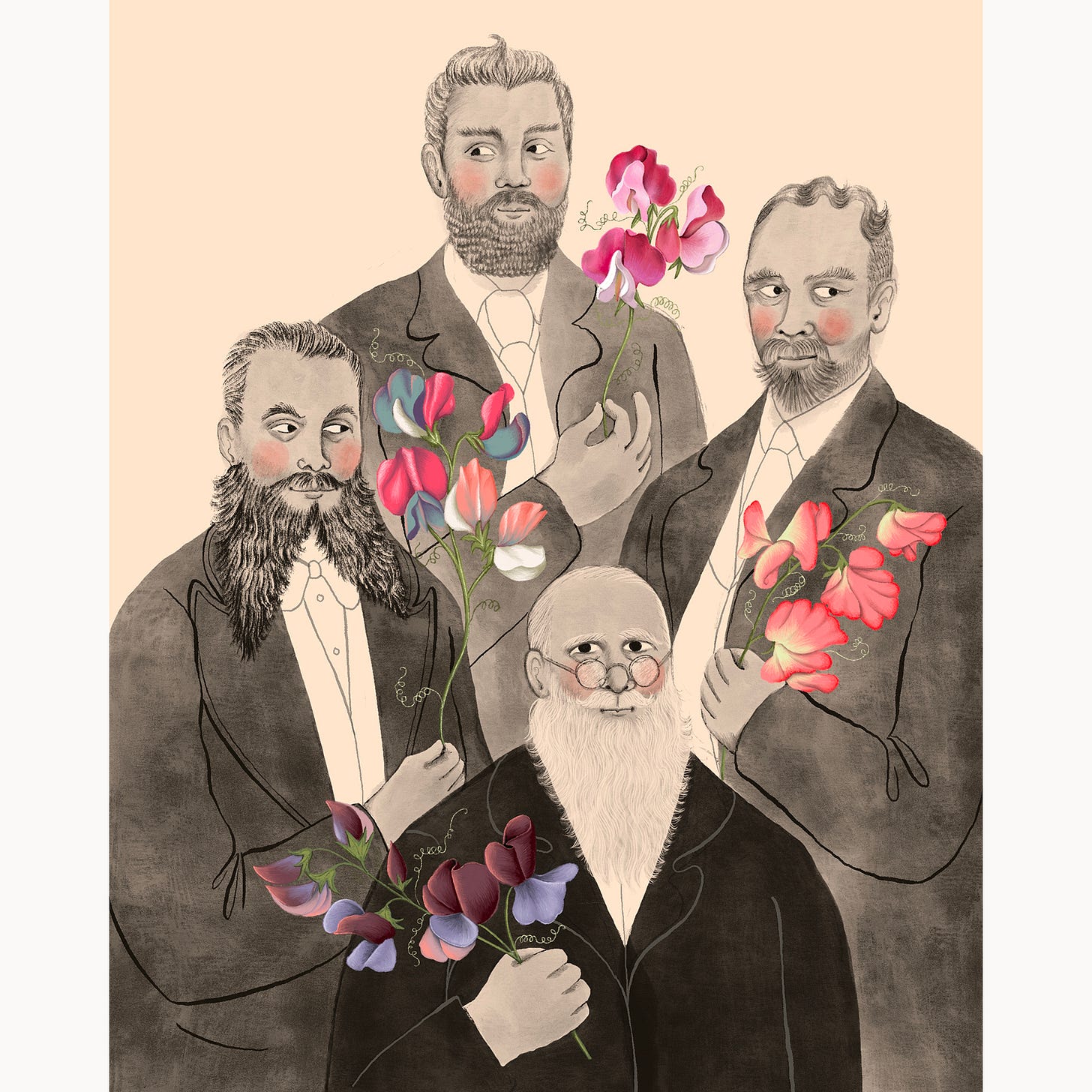

At the bottom of the garden, along the back fence, supported by an old bed frame, were Alan’s prized sweet peas. A profusion of blushing pink, and fairytale red, airmail blue, and velvet black, with a scent that hung in the air, intoxicating the bees and yellow butterflies, old men and small children.

Alan would name the flowers for us. That’s Miss Willmott, he’d say, That’s Lord Nelson, that’s Blue Shift, Black Knight, Painted Lady, Old Spice…

I wanted desperately to pick them.

The sweet pea has five petals—an outer banner petal, two folded petals and two inner petals. It is a delicate, quivering, bilabial, anatomical-looking flower. Or it looks like a butterfly.

From 1700-1900, many men devoted their lives to sweet pea propagation and diversification, pursuing variegated colors in deeper hues with frillier petals and longer stems.

Mr. Eckford, who grew wavy-edged varieties, was known as the Sweet Pea King.

Mr. Cole’s blooms were larger, but less fragrant.

Mr Burpee concentrated on harvesting stable seeds.

Mr. Cuthbertson wrote a detailed manual on “Sweet Pea Planting for the Average Man” which promised excellent results if the “work is honestly carried out.”

No-one has ever managed to grow a yellow sweet pea.

In 1911, 38,000 bunches of sweet peas were sent by train to the Crystal Palace in London from around the United Kingdom, each grower hoping to win a national competition with a prize of £1000, around $30,000 in today’s money. The first prize went to Mrs. Fraser in name only, the winning sweet peas were grown and shown by her husband, Reverend Fraser.

The photograph from the Royal Exhibition shows rows and rows of men in suits and hats proudly standing by their flowers. There might be some women but it’s hard to tell.

As far as I know, my great uncle Alan didn’t grow his sweet peas for exhibition, but I still wasn’t allowed to pick them.

They won’t last, he said. Better to leave them on the vine.

I would stand as close as I could get without trampling the plants, winding the pea tendrils around my fingers like a phone cord.

On that last visit, when we got in the car to drive away, Mac knocked on the window and passed through a sprig of Black Knight.

Alan waved his hat from the back fence.

I couldn’t know he would die a few months later.

I held the wilting sweet pea to my nose. By the time we got home it was crushed.

My mother helped me press it in a book.

A squashed black butterfly.

A blot.

It didn’t look like itself anymore.

But it also did. Some of its particles were redistributed. Some remained. Some still remain.

Well, I cried.

My Uncle Melvin and Aunt Wilma were my Mac and Alan. They preferred playing cards with my brother and me when we visited them instead of talking with the adults. Thank you for helping me revisit them this morning, Sophie.